In previous years, attending a startup demo day in Beirut—where hopeful graduates of accelerator programs present their projects and pitch for recognition and financial investments—tended to require a will to smile politely and some tolerance for boredom. But in September and October of this year, demo days and startup competitions with Lebanese entrants—some held in Lebanon and others international—proved to be exciting, prompting genuine smiles all around.

Officials and observers from accelerators and financial entities in the entrepreneurship ecosystem that Executive spoke with eagerly agreed that the startup pipelines this year are exciting. Such protestations from these players were, of course, unsurprising, but nevertheless convincing; they confirm that the passion and competence of startup teams, and the quality and diversity of the projects presented, are increasing.

The simple truth of this story is that the Lebanese entrepreneurship ecosystem’s ideation and innovation support machines are working. They are visibly improving the flow of appealing concepts and teams into the pipeline to becoming digital enterprises. In the process, the accelerators and support systems are, moreover, boosting their own quality.

This virtuous cycle is, this year, also being validated by the Lebanese startups’ performances in international competitions, most notably at the Gitex Technology Week in Dubai, held in October, where MAJ—a startup that Executive saw present at the Smart ESA demo day—claimed the best female-led startup trophy at a “future stars” competition. Speed@BDD graduate Ziad Alame, with his medical app “Spike,” beat an international field of over 200 competitors to win a “supernova” grand cash prize of $100,000.

The cherry on top of the small Lebanese ecosystem’s validation is the—in all likelihood temporary, but nonetheless appreciable—wave of tangible foreign attention that it has received this year, from the first staging of TechCrunch’s MENA startup “battlefield,” in early October at the Beirut Digital District (won by Lebanese contender BuildInk), and oil multinational Total bringing its corporate startup contest to Beirut this autumn, to the first Seedstars MENA Regional Summit to be held in Beirut, in November, and the 12th round of the MIT Enterprise Forum Arab Startup Competition, the finals of which will be held in December.

The quality and diversity of recent Lebanese entrepreneurship has impressed Executive. Following the editorial tradition of profiling hopeful startups, the magazine this year determined to make a topical selection of startups working in the fields of Fintech, engineering-related tech, and lifestyle apps with a Lebanese angle. We happily acknowledge that many other local startups with agro-industrial, educational, medical, gaming, retail, hospitality, data analytics, blockchain, and financial software development focuses have also recently arrived in the ecosystem, but decided to narrow our selection to the aforementioned three sectors, with an extra look at Lebanese Fintech that was launched in the region.

Having neither the resources nor the time to produce a qualitative ranking of the portrayed startups, Executive editors profiled those that excited them on first contact—from innovative e-commerce marketplaces and lifestyle apps full of promise, to tech apps that radiate the potential to make a difference in important industries, and Fintech startups that aspire to serious social relevance.

Anachron Technologies

According to Anachron co-founder Wael Khattar, the robo advisory venture solves two problems. “For banks, we open new markets, as we solve the problem of how to reach clients that they were unable to reach profitably in the past,” Khattar says. “To clients, we offer easy, quick, and professional personalized investment advice at low cost.” Working at local banks, the founders of Anachron experienced how these banks’ investment advisors faced challenges in meeting the needs of people who wanted to deploy moderate amounts. Seeing how bank staff’s interactions with non-high net worth individuals regularly caused frustrations to clients and constituted inefficient use of human capital for banks, Kawas and Khattar embarked on developing a hybrid concept, whereby use of the robo advisor will allow the human investment advisor at banks to decrease the time required to serve one client, from 1.5 to 2 hours to five or 10 minutes. Khattar says competitors for Anachron include existing investment advisors, brokerage houses, and new B2C robo advisories in the region. He emphasizes that the startup will not give investment advice, but will rather provide banks with a platform to give investment advice more efficiently. Under Anachron’s proposed revenue formula, its revenue generation will be determined by how many clients the banks acquire. “In our model, banks will take 0.5 to 1 percent of assets under management as fee and Anachron will take 20 to 25 percent of what the bank charges,” Khattar says, describing the scenario as win-win for the startup and its partner banks, since Anachron’s economic goals will be met through revenue-sharing, while the banks will be able to acquire investment clients that they could not otherwise serve.

Buildink SAL

Significantly reducing building times and the labor demand of construction projects is the promise of 3D printing startup Buildink. CEO and co-founder Bilal Farshukh says the idea for the startup was borne out of frustration at seeing delay after delay during the one and a half year construction of his two-story family home. Farshukh tells Executive that the startup’s 3D printer can reduce construction times by up to 75 percent compared to traditional building methods, and is able to cut labor costs by reducing the number of workers needed on the build site.

Farshukh sees Buildink as a construction industry disrupter due to its potential to slash costs and build times. He says the current prototype, a proof of concept cable robot printer—measuring 2x2x2 meters, with an operational size a little smaller than the dimensions—is designed to construct small- and medium-sized projects like outdoor benches, animal shelters, or any design that fits the dimensions. The startup is now in talks to sell its services to a regional multinational construction firm, and is seeking an investment of $400,000 to design and build a larger cable robot printer with an operational range of 10x10x5 meters.

Farshukh says regional construction firms should use Buildink’s 3D printer instead of the competition, because importing the technology and material is expensive. The startup offers printing material locally, and Farshukh says their design is easier to install and remove from build sites.

Crowd powered

Ever wondered whether you could harness the rays of the sun to power your business or home, but didn’t know where to start? Crowd Powered has your back, offering a web-based platform that helps customers determine whether they have the space for solar panels, and which solution would be affordable for them.

CEO and co-founder Georges Khoury says the problem is that Lebanese solar is a fragmented market, in which potential customers have to find the right renewable solution for their available space and budget, shop for a loan, and hire a design office, equipment supplier, and contractor to get solar panels installed on the roof and under the sun. “Nobody [else] can give you a turnkey solution. Crowd Powered offers a one-stop-shop designing, securing financing, and installing renewable energy solutions for businesses and homes,” Khoury tells Executive.

He says the startup could help Lebanese businesses and homes save money on their energy bills by customizing solar solutions to fit each customer’s budget and space, and lessen their reliance on costly generators to fill the gap in supply from the state utility. The next phase, as part of the pitch for a new injection of cash, will be twofold: a push into the large Saudi Arabian market, where owners of solar installations can sell their excess electricity to the public utility; and to develop software that Khoury says will help potential customers conceptualize what adding renewable energy to their power mix will do to the load profile (the amount of electricity on the grid), along with the savings potential and needed capital expenditures.

Fabricaid

Fabric Aid’s mission is to sell affordable second-hand clothing (priced between 500LL and 3000LL) to underprivileged communities, solving an impact problem on several levels.

After a chance revelation that the clothes he was donating were going to waste, founder Omar Itani investigated and discovered that NGOs struggle with clothing donations because storing and redistribution costs them time and money. Meanwhile Lebanon’s estimated 250 second hand stores import clothes from abroad. With an estimated 2.5 million refugees, and thousands of Lebanese living in poverty, there is huge demand for affordable clothing. On the other hand approximately 16,000 tons of new clothes are consumed annually by a different tier of residents, who donate large quantities regularly. What Itani found was a lack of infrastructure to transfer unneeded clothes from the latter to fill the needs of the former.

Fabric Aid sources clothes through two channels: NGOs are paid per kilogram for what they collect, and from a network of donation boxes. Only clothes in good condition are selected. FabricAid keeps track of its inventory with the help of a proprietary algorithm, hashtag-based data system. The items are retailed at pop-up shops at NGOs or refugee camps, a permanent shop near Saidon (a second store is opening soon in Beirut), and also sold to second hand shops at prices cheaper than their imported counterparts. Damaged clothing is upcycled into pillow fillings, crafted by an orphanage, and to be used as part of an upcoming recycled-furniture project. One of the solutions for donations that are too revealing or otherwise inappropriate is another upcycling project with fashion schools.

FabricAid plans to export clothing and franchise outlets in the region, and to one day offer affordable second-hand clothing in communities around the world.

Dox SAL

Knowing when exactly to change the battery of an electric vehicle is measurable, says Nicolas Jamal, a dox co-founder. Dox was originally conceived as a drone startup, but changed tack after seeing opportunity measuring battery performance of electric vehicles and predicting when batteries should be replaced. The problem, Jamal explains, was that companies had been wasting money by discarding their batteries before the end of their life cycle. The startup has identified the burgeoning electric vehicle market as its target and hopes to offer its proof of concept, using real-time battery data, to an automobile manufacturer by the middle of 2019, and to then close a deal to go into production by the end of that year.

Jamal notes that the dox solution, as plug and play software, is cheaper for automakers to integrate into vehicle computers than the alternative—hardware solutions offered by competitors that require satellite connection to transmit and store data in the cloud. Some automakers are designing inhouse optimization solutions, but Jamal says dox can still capture a slice of the electric vehicle battery market—which is expected to grow in total vehicle market share compared to internal combustion engine vehicles—and could be a player in the battery industry in general.

Hjezle

Hjezle—which means “book for me” in Arabic—makes it quicker and easier for users to book last minute beauty appointments at nearby salons, via an online chatbot and soon-to-be-launched mobile app. CEO and cofounder Jana Rouhban realized that she and many other women were too busy to spend time calling several salons looking for beauty appointments, prompting her to research the idea of online beauty bookings. The concept exists outside Lebanon, but Rouhan—who credits Smart ESA with helping her fine-tune the idea—reached out to beauty parlours and clientele to tailor it to the local market. Originally, she had wanted to make Hjezle a regular beauty booking website—not necessarily for last minute appointments—but most Lebanese salons are not yet systematized enough for this to be feasible.

Lebanon does not have a last minute booking platform for any services, and boasts only one other platform for making beauty appointments—though it has not officially launched and is not focused on last minute bookings specifically.

Hjezle connects beauty salons to new clients, charging them a percentage of the value of the bookings made on the platform, while facilitating users’ last minute bookings for free. Rouhban says other countries in the region could benefit from the service too—the startup is looking to expand to fast-paced Dubai soon, perhaps within the next year.

Juno

Juno co-founder Alexander Axiotiadis predicts that the displacement of large populations is likely to continue or worsen in the future. Banks will face many challenges in coping with this, but mobile apps and app-based cards will play a crucial role in such an environment, the Lebanon-born and raised Axiotiadis tells Executive. With years of experience in providing mobile financial solutions to customers in Greece, the founders of Juno are determined to pilot payment and transfer services for unbanked and underbanked populations in Lebanon, while satisfying minimal KYC requirements. Under financial inclusion imperatives, Juno aims to incorporate local, migrant, and refugee populations into a digital banking service, at very low cost even for international usage. “Our costs [for the client] are one or two times lower than any bank. Moreover, banks cannot afford to target the populations we are targeting as clients, because onboarding will already be so expensive for them that it doesn’t pay off,” says Axiotiadis. According to him, a few competitors exist in the app space, but none are geared toward exactly the same activities. The company’s revenue formula is based on fees for transactions. Additional revenue streams could be derived in the future from data mining and premium services, but these are long-term ideas. “Juno is a social empowerment tool and financial tool for all those people who need to organize their lives and their families financially, and want a chance to be included in financial systems and the financial economy,” Axiotiadis says.

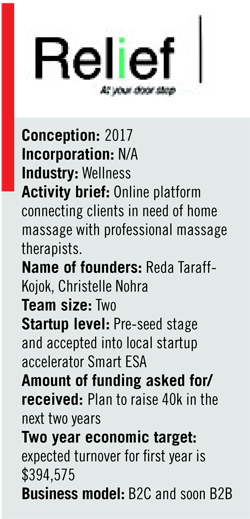

Relief

Relief makes it possible to use an online platform to book a massage in your own home with a certified therapist. After some research, founder and massage-lover Reda Taraff-Kojok realized that no such service existed in Lebanon, but that the demand did—so he launched the startup himself, jumping into the growing wellness market in the country. Though some prefer the ambiance of a spa, Taraff-Kojok found that many people are more likely to get massages if they do not have to waste time driving to and from the appointment. After an initial testing phase, he figured out the logistics and best practices for in-home service: therapists will bring equipment (massage tables, oils, music, towels, etc.) with them to the premises, unless clients request otherwise. Because of the unfortunate association of massage with sexual services, he has carefully verified 30 Lebanese massage therapists, looking for experience. This process was one of the initial challenges in producing the business, as many individuals and organizations were doubtful of his intentions.

Relief, which should be up and running by the end of 2018, will offer various massage types (deep tissue, Swedish, etc.), each for $68 per hour—along with various discounts and package deals—which can be paid online by users. Clients will be able to rate the service they receive and can request specific therapists when booking. Tarraf-Kojok is turning some of the existing competition into partners, offering independent masseurs the opportunity to use his platform in exchange for 30 percent of their earnings. The platform will later include private yoga sessions paired with massage. Further down the line, Taraff-Kojok plans to expand by offering in-office services—shoulder-massages offered to teams in bulk—an idea he picked up from Japan. Relief is expected to expand regionally, first to the UAE, where the founder anticipates stricter regulations for the home service, such as rules on the gender of therapists deployed to clients.

Mint Basil Market

Like many entrepreneurs, Mint Basil Market co-founder Vanessa Zuabi was trying to fulfil personal needs and stumbled upon a business idea that now seems to be resonating with others in Lebanon. Having been diagnosed with a condition that forced her to adopt a healthy diet and lifestyle, she had a hard time sourcing products that she needed, as most were rare to come by. Mint Basil Market is a website where users can buy a range of healthy products in one place and get them delivered for free all over Lebanon. The startup works with almost 50 suppliers—many of them local—offering healthy, natural, and organic food, as well as beauty and cleaning products, catering to a growing number of wellness-conscious consumers in Lebanon. At less than a year old, the startup has a 50 percent customer retention rate, higher than the industry standard of 20-30 percent according to the founders.

Zuabi and co-founder Lara Noujeim say the company goes beyond e-commerce and is building a community. The website includes recipes, health tips, articles by nutritionists and health coaches, videos, and more to help users make healthier choices and better purchasing decisions.

Mint Basil Market has started to test the possibility of starting a white label range; its first collaboration with Lebanese Chef Lara Ariss was one of their top-selling products when launched. This will enable them to have a higher margin. A mobile app is launching next year, and the startup has plans to launch in other regional markets.

Rumman

“We are solving a universal problem that exists mainly in the global south, which is the lack of access to affordable savings and investment platforms,” says rumman co-founder Shurouq Qawariq. With its mobile app, the Fintech startup tackles a global problem that is especially pressing in the environments of Palestine and Lebanon. According to Qawariq, the founders reconnected last year in London. Incensed by the vast difficulties each faced in their daily financial dealings, they decided to start something together. “We really liked idea of micro-savings and micro-investments, partly because it makes [the process of] growing capital accessible to the masses,” Qawariq tells Executive.

The app’s hook for enticing savings-agnostic clients is the option to automate small savings by rounding up users’ incidental purchases—even your qahweh or shawarma. The app will aggregate these small roundups, and then channel them into investment funds via banks. As Qawariq explains, the founders revised their startup idea into a model involving partners, such as banks on one side of the value chain, and payment collection networks on the other. “The cool thing with rumman is that clients can invest as little as they want and have visibility of their investment portfolio,” she explains, adding that clients will have several options to expand their investment sourcing. Competition entails similar Fintech startups and emerging online banks in the region, she says. rumman’s monetization concept is to charge banks per user, plus a percentage of the profits that banks realize from investing users’ funds.

Sarwa Digital Wealth ltd

According to Nadine Mezher, co-founder of Sarwa, the ideas that led to Sarwa were conceived two years ago by her two co-founders, who were then working in the Canadian financial sector. Having arrived in Dubai, where the Dubai International Financial Center had inaugurated the region’s first dedicated Fintech Accelerator program in early 2017, the two met with 10-year Dubai resident Mezher. “The more we worked together, the more we realized how much a robo advisory is needed and missing in the UAE market, and that the market is ready for it,” Mezher tells Executive. Fueled by personal anecdotes, the desire to encourage a culture of saving and investing in Arab countries, and to alleviate the effects of the region-wide paucity of pension funds and retirement plans, the three established Sarwa, with a first-mover advantage as an Arab World-based hybrid robo advisor focused on conventional finance (as opposed to Sharia-compliant Fintech). The company became operational in February 2018 and quickly achieved first revenues. According to Mezher, Sarwa relies on comparably affordable exchange traded funds (ETFs) as investment choices and offers services to clients (UAE residents only until the full license is approved) on the basis of opening an account with a minimum balance of $2,500. Under its fee-based revenue model, the firm charges 0.85 percent of the account balance as annual advisory fee, with no opening or exit fees. Near-term targets include acquisition of a full license and regional expansion. “Sarwa is about democratizing the wealth management environment in a country, and [about] making investment available, accessible and affordable for everyone, regardless of net worth,“ Mezher says.

Wanowi

Originally thought up as an online fashion auction house, the current version of Wanowi caters mostly to the trendy kids of Generation Z in Lebanon and the region who wish to buy or sell clothing items, shoes, and accessories. The online marketplace connects demand and supply of popular international streetwear brands like Supreme and Off-White, and limited edition products, most of which are not available in retail stores in Lebanon. Inspired by her fashion savvy adolescent children, founder Dina Daher tested the waters by putting up a rare t-shirt, and received over 100 requests in one day—which, to her, was a clear indicator of high demand in the market.

The startup itself does not hold sellers’ inventory, and focuses on logistics—picking up items from sellers and delivering them to buyers—and processing payments between the two parties, as well as maintaining a social-network style platform, where people can connect, discuss, and negotiate prices.

In addition to giving an opportunity to private sellers, Wanowi has also begun testing the idea of selling a few items themselves. High demand means markup is also high—the business takes a 15 percent cut of user’s sales and a 30 percent markup on the sale of their own items.

Today there are about 150 sellers on the platform. So far, sellers can be based in Lebanon or the UAE, but Wanowi delivers throughout the region and plans to list sellers from other countries in the region (pending logistics). Buyers have 15 days to return products if they don’t fit the description exactly, and sellers aren’t paid until after this period. Daher plans to expand to other markets in the region, and is looking to open a physical retail space