Many believe that there is no such thing as too much money. At a closer look, however, the extreme abundance or absence of wealth both appear to be prime causes of anguish, albeit in incomparable proportions. Even moderate and temporary cases of poverty lead to all manner of problems, from stress and sleeplessness to ulcers and constant headaches; the poor are often denied their rights to dignity, housing, a clean environment, safe water and food, education, healthcare, labor, and freedom of movement.

It is also true that more people stress over the absence of wealth than those who suffer due to extreme riches. However, this is only the case since the precariat, and the extreme poor outnumber the wealthy by such huge margins.

Adjusting of premises: Poverty is no self-inflicted epidemic and wealth no sign of geniuses

For each billionaire there are millions who languish in extreme poverty. Yet there are many reasons why wealth is not headache-free. One is that wealth is not an existential and intrinsic quality, but a secondary or external property that, as such, is of limited existential value. The third millennium’s dominant cultural norm on wealth and the afterlife is that “you can’t take it with you.” The historic belief systems whereby people adorned corpses with food supplies and possessions for the hereafter are, by and large, as dead as the Pharaohs.

Moreover, in social terms, wealth restricts your networks, which, since the emergence of the post-industrial era, increasingly constitute your social capital. As a high-net-worth-individual (HNWI) with a streak of exhibitionism, you might have millions of insincere “followers” and “friends” on social media, but loneliness appears to be one of the first trade-offs that comes with wealth.

Next, in our money-obsessed global capitalist culture, wealth tends to lead its possessor to form a dependency on what Nassim Taleb described as “constructed preferences” in his 2017 musings “Skin in the Game.”

“When people get rich, they shed their skin-in-the-game experiential mechanism,” wrote Taleb, by which he meant that the newly rich lose their own preferences and substitute them with preferences constructed and pushed upon them by people who want to sell them something. In so doing, he says, the rich complicate their lives unnecessarily and trigger their own misery, but—because they are rich—without even having the benefit of being acknowledged as victims of their exploiters.

These pressures of constructed preferences appear to get exacerbated with possibly increasing frequency in resonance with external impacts of economic cycles that for the past ten years have appeared to be less and less predictable. In 2018, volatility and uncertainty cloud markets and shape the language of wealth managers and investment advisors—which tends to result in mixed signals and confusion.

Mid-2018 observation checkpoint: Examples of constructed preferences and their signaling

Just this summer, in July and August, some top names in international wealth advisory appear to have cranked up their bullshit generators even while admitting to heightened levels of uncertainty in the economy and financial markets. That there is confusion over the investment outlook for this year can be surmised by reading statements from institutions such as Goldman Sachs. The investment bank in July issued an—as the bank admitted, unusual—mid-year update to its 2018 investment outlook with this header: “Ebb and flow between steady and unsteady factors continues unabated.”

The updated outlook informed readers that Goldman Sachs sees a close to zero likelihood for a recession in the US in 2018, while projecting a 10 percent probability of a recession by mid-2019. Beyond that, it constructs a balance of steady factors—such as economic growth and a low probability of recession—with some unsteady potential influences—from terrorism, populism, cyber attacks, global political tensions, a cyber-currency craze, and domestic politics in the United States—and concludes that the tug of war between steady and unsteady factors has intensified since early 2018 and will continue unabated.

Another US-based financial services group, BBVA Compass, noted “concerns surrounding the financial health of the business sector,” which it described as justified to some extent. The firm shared its view that “market participants are worried that higher price pressures, faster monetary policy normalization, and a trade war, amid stretched valuations, could trigger a significant decline in risk appetite,” and warned that the convergence of several problem factors could, at non-specified times, cause “a major asset price correction” and “bring about an economic recession.”

Meanwhile, the mid-year investment outlook by investment management company Blackrock, also published last month, noted that greater uncertainty along with rising interest rates “has contributed to tightening financial conditions and argues for building greater resilience into portfolios,” even as it opened its outlook with reference to its base case scenario of “strong U.S. growth extending positive spillover effects to the rest of the world, sustaining the global economic expansion.”

American financial weekly Barron’s reported in late August that wealth advisors are counselling clients to stick to their “core values,” naturally without attempting to offer any suggestion of what that could mean. “It’s not that wealthy families shouldn’t buy a Ferrari. It’s that purchases of any size should be made in the context of core values and principles as well as what individuals see as the ‘desired outcome’ of their wealth: to preserve it, grow it, or spend it down (which could include giving it away to charity),” the weekly said, as it presented activities by a team affiliated with Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Private Banking and Investment Group, which chases ultra-HNWIs.

Wanted: New definitions and better answers

With this deluge of messages aiming to sell the rich products that would profit the salesmen, it’s no wonder that the wealthy are doing what they can to mask the existential unimportance of their manifold assets. This makes it ever more imperative for society and the wealthy to look for any potential means of stimulating a paradigm shift on global wealth.

Global wealth is increasing despite all of the Minsky moments and episodes of creative destruction this century. According to the most recent Global Wealth Report by the Credit Suisse Research Institute (CSRI), the growth rates of global wealth have slowed from 2007 onward, but wealth has overall continued to rise. Not only did it reach in excess of $280.3 trillion by mid-2017, and was up 27 percent from $220.9 trillion at the onset of the Great Recession in 2007, but CSRI estimated global wealth to reach $341 trillion by 2022, or $60 trillion more than its estimate for 2017.

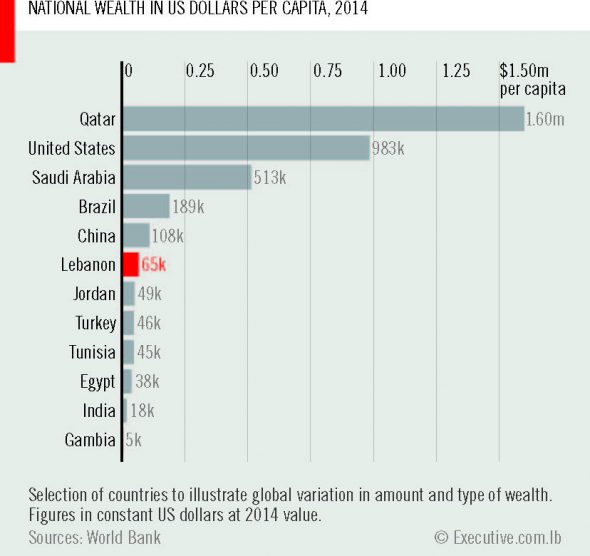

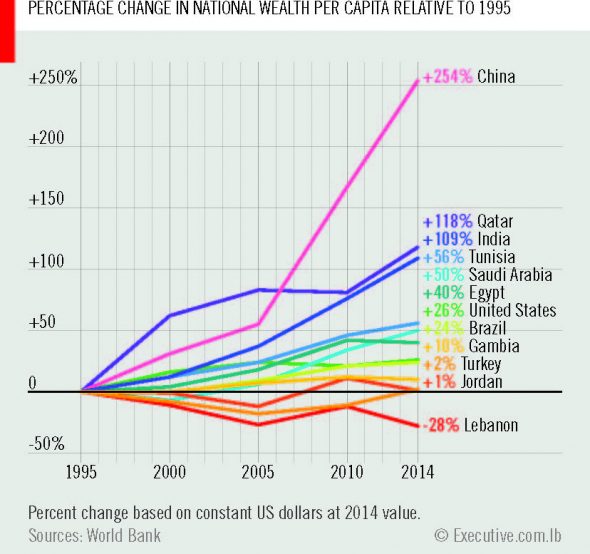

This relentless accumulation of wealth makes new methodologies for wealth measurement all the more interesting. The World Bank has used such a methodology in its publication “Changing Wealth of Nations 2018,” in which it calculated total wealth per nation per capita in a bottom-up approach that considered four wealth components: natural capital, produced capital, human capital, and net foreign assets.

Elaborating further, the report notes: “A nation’s wealth consists of a diverse portfolio of assets, which together form the productive base of the national economy. These assets include:

Natural capital—including energy (oil, natural gas, and coal), minerals, agricultural land (cropland and pastureland), protected areas, and forests (timber and some non-timber forest products);

Produced capital—including machinery, structures, equipment, and urban land;

Human capital—including the knowledge, skills, and experience embodied in the workforce; and Net foreign assets (NFAs)—including portfolio equity, debt securities, foreign direct investment, and other financial capital held in other countries.”

According to the World Bank, the approach used in Changing Wealth of Nations 2018 marked “a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth, and then calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption.” Under the previous top-down approach, calculation of produced and natural capital and NFAs and their subtraction from total wealth led to a residual of “intangible capital” attributed mainly to human capital. “Now with a direct measurement of human capital, total wealth can be estimated as the sum of all categories of assets,” the explanation of methodology concluded.

As Kristalina Georgieva, chief executive officer of the World Bank, explained in the report’s foreword, the World Bank used the new approach in seeking to measure “comprehensive wealth.” For this, the bank could for the first time ever attempt an estimate of human capital in each of the 141 countries covered in the report by drawing on a database of more than 1,500 household surveys maintained by the World Bank. According to Georgieva, the new approach is hoped to set the stage “for addressing development through a comprehensive measure of wealth, which underpins income and well-being,” and to contribute to better policy making for economic progress on national and international levels.

Another interesting new development in international wealth and growth debates is a tendency to move beyond the century-old fixation on gross domestic product (GDP) as a central measure for a country’s economic health. Even the CSRI has recently focused more on taking a new direction on GDP, publishing a report in May that questioned the assumption that GDP adequately reflects the state of the respective society. The report—called “The Future of GDP”—argues that that weaknesses of GDP metrics need to be discussed further and responded to by policy makers and economic stakeholders. Further, it calls for public and private decision makers to deploy the many instruments they have at their disposal for complementing GDP measurements with better assessment of impacts on societies and the environment.

Asked by Executive about his views on GDP for measuring economic health and performance in Lebanon and in general, Marwan Barakat, chief economist of Bank Audi, concurred that there is new ground to be broken. “While GDP remains a main and widely acknowledged measure, it should by no means be the only one used to measure economic performance and progress,” he says. “It should rather be complemented by wealth and equality measures taking into account social, technological development and perhaps environmental factors so as to gauge economic expansion and growth dynamics in a more comprehensive manner.”

Add in: The inequality equation

That inequality is not something that can be made extinct does not mean that certain levels of inequality are unproblematic. If inequality is left to fester, it can balloon into a massive social problem. This seems to be on the table for Lebanon. In an Executive contribution in 2014, the chair of the Economics Department at the Lebanese American University, Ghassan Dibeh, noted that Lebanon is one of the world’s most unequal countries in terms of wealth distribution, “with around 66 percent of the adult population owning less than $10,000.” He warned “the economy will continue to wobble” under continued low tax rates on capital and profits in combination with a high public debt burden and increasing “power of the rentier class in the economy.”

Lebanese economist Roy Badaro separately agrees that the problem of economic inequality was not taken seriously by political decision makers in the past, but says he sees more and more people in political parties waking up to the repercussions of inequality—which Badaro views among Lebanon’s most serious economic problems. He describes the current state of inequality in the economy as having reached the end of the road.

“As an economist, I am very sensitive to inequalities in Lebanon,” he tells Executive, adding that the national savings issue, which is intertwined with the country’s inequality problem, is in urgent need of being addressed. “There is no economic prosperity if the private savings rate does not get much higher and if there is no negative savings rate in the government,” Badaro says. “Having a negative savings rate for large parts of the population [as is strongly suspected to be the current situation] is very detrimental because it is not sustainable in the long term, so we have to find a solution for these people and the best solution is to decrease the cost of living, not to increase salaries.”

With the infographic charts in this overview, Executive can give our readers some impression of the contributions of human capital and other significant intangible assets that are made more accessible for the calculation of Lebanese per capita wealth under the multi-factor bottom-up methodology deployed by the World Bank in Changing Wealth of Nations. The report’s authors describe human capital as the largest component in global wealth; this approach is reflected in the numbers given, as the value for total global wealth is $1,143 trillion in 2014—much higher than estimates given by reports using other methodologies.

According to the World Bank, wealth increased by 66 percent from 1994 to 2014. The much higher estimate of global wealth under the World Bank’s approach might be considered an indication that wider consideration of wealth components—eventually even including attempts to somehow quantify social capital so that it can be better recognized and developed in national economic contexts—is an attractive avenue to explore.

In looking at wealth and inequality, one must acknowledge that labor compensation systems and many other ways in which societies today assess wealth require much fundamental work.

Add: Computable data and inclusion

One issue in this regard is understanding the size and concentration of national and household savings in Lebanon. Nassib Ghobril, the chief economist of Bank Byblos, points to the high deposits in the banking system. He says these are clear indicators for significant savings in Lebanon, but concedes that there is no official information on the savings rate and no information regarding its distribution by income group. No analyst or financial industry stakeholder could tell Executive to what degree savings are concentrated with the top wealth group.

All who confess adherence to the concept of existential human equality are best advised to cherish wealth and work for increasing the wealth of the nation writ large. To this end, the financial system can play a significant role on the microeconomic and technical level, if it is capable of getting more vertically aligned with the interests of client groups across the social spectrum.

Society needs the rich and the poor. Inclusion by banks cannot be limited to financial inclusion, and banks should focus on allowing access to services that most adequately reflect each client’s needs, rather than focusing only on private banking. Small steps in the right direction can be seen in financial industries, such as life insurance , and microfinance.

If economic mobility is taken at the level of the individual, a lifetime can see one move across the spectrum of poverty to wealth, with added complexity due to individual perceptions of each extreme. One can take lessons in this regard from Seneca, the stoic Roman billionaire who once influenced the young Emperor Nero before being forced into suicide by his one-time charge. A member of the one percent, he wrote of poverty: “Non qui parum habet, sed qui plus cupit, pauper est.” (Not he who has too little but he who craves more, is poor).

Note: Countries represented in the infographics in this overview have been selected for illustrative purposes. The countries show the breadth of the wealth spread and their selection does not imply any shared category or grouping.